”A central issue from a consumer behavior perspective is the extent to which an owned object serves the functions of defining and maintaining the self-concept or identity of a consumer. One would expect different affects and behaviors toward an object that serve these functions than toward an object that does not. One protects and cultivates one’s self. For example, if a home, piece of furniture, article of clothing, and so on constitute part of a consumer’s identity, we might expect more protective behaviors, greater effort spent on maintaining the object, and greater emotional difficulty in accepting deterioration or loss of the object.”

As Dwayne Ball and Lori Tasaki (1992) explain in the quote above, product attachment is a result of people’s tendency to support their identity with their belongings. Studies (Belk, 1988) have shown that personal possessions are used to develop one’s identity as well as reminders of one’s self-image. Furthermore, people express their identity with objects they associate themselves with publicly while using them to integrate in social environments as well. However, in regards to product attachment, the importance of pleasure provided by products has also been discussed recently (Mugge, Schifferstein and Schoormans, 2008).

Product attachment is an important factor in post-purchase consumer behavior. In addition to extending use that can be seen to lead to more sustainable consumption, becoming attached to a product will most likely give a positive impression of its manufacturer. This can increase brand loyalty and purchase readiness towards the company’s other products while making people inclined to recommend the company to others as well. Recent literature even provides product design guidelines for supporting the creation of emotional bonds between products and their owners. According to current view, product attachment can be facilitated with product features that promote self-expression, increase social interaction, help to attach memories to products and provide pleasure. (Mugge, Schifferstein and Schoormans, 2008)

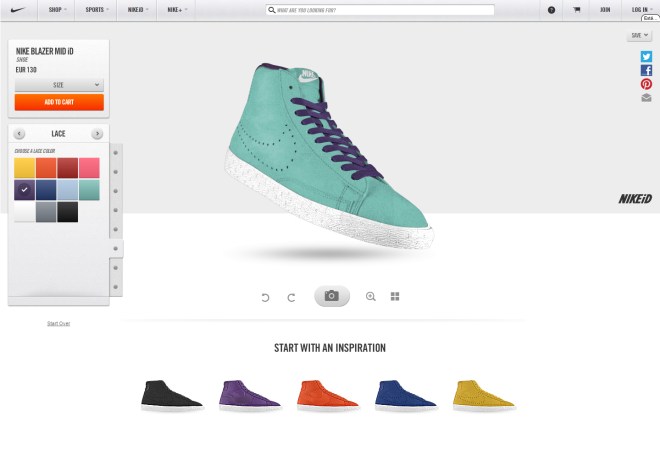

Figure 1. NIKEiD is an online application that allows customers to personalize their shoes. (Nike Inc., 2013)

Figure 1. NIKEiD is an online application that allows customers to personalize their shoes. (Nike Inc., 2013)

Figure 2. A tandem bicycle has the potential to increase social interaction. (Lee, 2011)

Figure 2. A tandem bicycle has the potential to increase social interaction. (Lee, 2011)

Materials offer great many ways to affect emotional relationships between people and their possessions. Because an emotional attachment can be seen to comprise of reflective experiences that in turn are based on immediate sensations (Demir, 2008), materials’ physical properties are directly related to product attachment. One interesting possibility is to make products more pleasurable by creating surprises with incongruities between materials’ visual and tactile properties. Another one is to adjust products’ wear behavior through materials selection to allow them to age gracefully; to withstand use but also show signs of the history they share with their owners.

Figures 3–4. Products that can help memory retrieval: a cookie jar that releases the scent of vanilla and a pair of worn out jeans. (Rakuten, 2018; Thompson, 2011)

Figures 3–4. Products that can help memory retrieval: a cookie jar that releases the scent of vanilla and a pair of worn out jeans. (Rakuten, 2018; Thompson, 2011)

In addition to materials’ tangible properties, product attachment can be facilitated by meanings embedded in them. The most straightforward way to do this is to employ individual meanings relevant to a person’s identity that can be related to things such as monetary value or environment-friendliness. A more challenging approach is to use one or several materials to construct combinations of meanings that are more personal and can refer to, for example, a certain kind of life style. Still, probably the most effective way to support product attachment by materials is to manufacture products using particular pieces of materials that carry memories or stories meaningful to their eventual owners.

Figure 5. Imagine owning a piece of furniture made of a fallen tree from the backyard of your childhood home. (Kaje, 2010)

Figure 5. Imagine owning a piece of furniture made of a fallen tree from the backyard of your childhood home. (Kaje, 2010)

Long-term research studying relationships between people and their belongings is needed for creating methods to systematically facilitate product attachment. On the other hand, it’s equally important that designers try to apply the information already available. Not only can these experiments produce extraordinary products but also act as conversation starters that help advance the research of consumer behavior in general.

References

Ball, A. Dwayne & Tasaki, Lori. 1992. The role and measurement of attachment in consumer behavior. Journal of consumer psychology, 1(2), 155–172.

Belk, Russel. 1988. Possessions and the extended self. Journal of consumer research, 15(2), 139–168.

Mugge, Ruth, Schifferstein, Hendrik & Schoormans, Jan. 2008. Product attachment: design strategies to stimulate the emotional bonding to products. In Product experience edited by Hendrik Schifferstein & Paul Hekkert, 425–439. Amsterdam: Elsevier science.

Nike Inc., 2013. NIKEiD. [Online] Available: https://www.nike.com/us/en_us/c/nikeid

Lee, M., 2011. Tandem. [Online] Available: http://www.flickr.com/photos/openmike/5751798859/

Rakuten, 2018. Alessi Mary Biscuit. [Online] Available: https://global.rakuten.com/en/store/cds-r/item/h-370/

Thompson, C., 2011. Worn Out. [Online] Available: http://www.flickr.com/photos/claire69/5454808947/

Kaje, 2010. A Swing Without. [Online] Available: http://www.flickr.com/photos/kajeyomama/4987980859/

Demir, Erdem, 2008. The field of design and emotion: concepts, arguments, tools, and current issues. METU Journal of the faculty of architecture, 135–152.